Acoustic modeling allows you to identify phonemes and transitions between them. But we still miss a step to return proper words: a language model that helps identify the correct words.

Language model integration

Recall the fundamental equation of speech recognition:

\[W^{\star} = argmax_W P(W \mid X)\]This is known as the “Fundamental Equation of Statistical Speech Processing”. Using Bayes Rule, we can rewrite is as :

\[W^{\star} = argmax_W \frac{P(X \mid W) P(W)}{P(X)}\]Where \(P(X \mid W)\) is the acoustic model (what we have done so far), and \(P(W)\) is the language model.

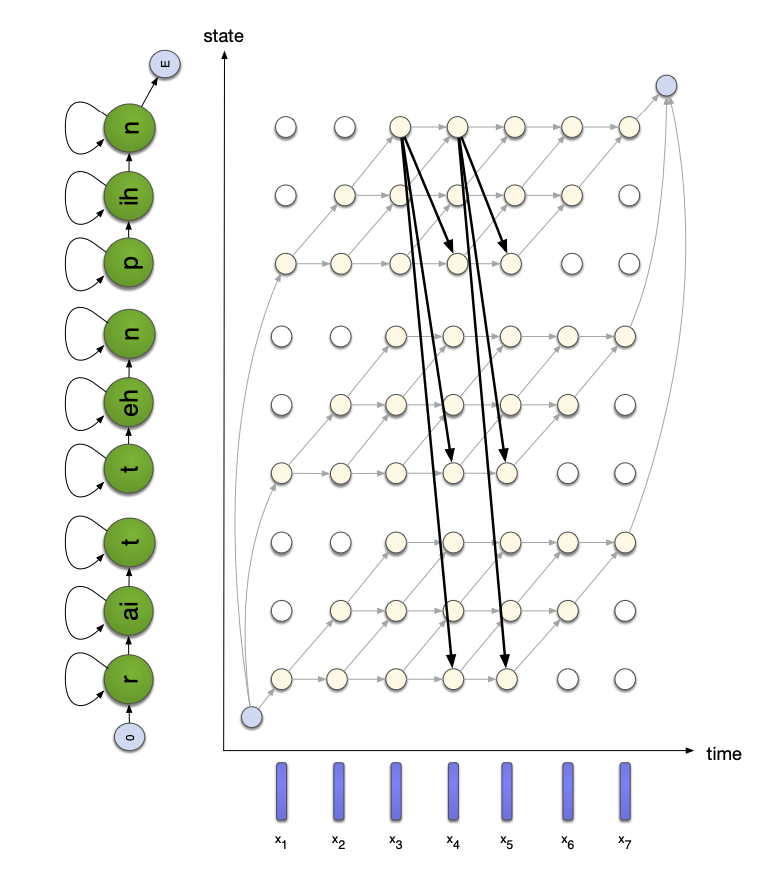

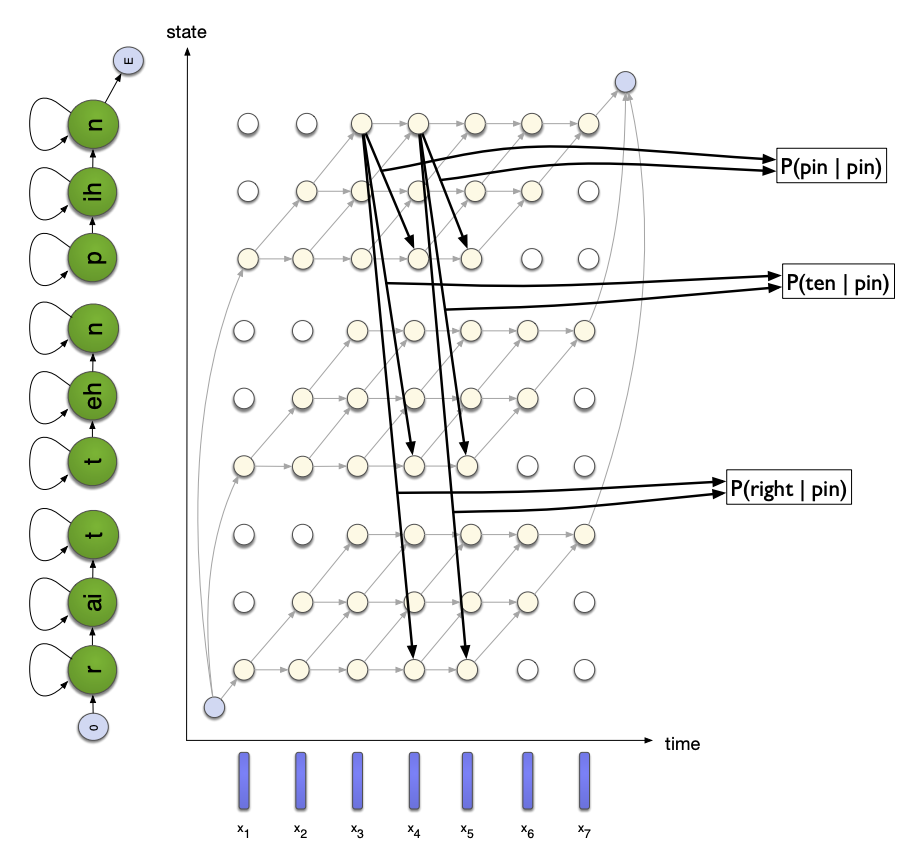

In brief, we use pronunciation knowledge to construct HMMs for all possible words, and use the most probable state sequence to recove the most probable word sequence.

In continuous speech recogniton, the number of words in the utterance is not known. Word boundaries are not known. We therefore need to add transitions between all word-final and word-initial states.

If we then apply Viterbi decoding to find the optimal word sequence, we need to consider \({\mid V \mid}^2\) inter-word transitions at every time step, where \(V\) is the number of words in the vocabulary. Needless to say, it can become a problem that is way too long to compute. However, if the HMM models are simples and the size of the vocabulary is small, we can decode the Markov Chain exactly with the Viterbi decoding.

So the question becomes: can we speed up the Viterbi search of the best sequence using some kind of information? And the answer is yes, using the Language Model (LM).

Recall that in an N-gram language model, you model the probability of observing \(w_i\) after a sequence of words \(w_{i-n}, w_{i-n+1}, ... w_{i-1}\)

However, the exact search is not possible for large vocabulary tasks, especially in the case of the use of cross-words. There are several solutions to this:

- beam search : prune low probability hypothesis

- tree structured lexicons

- language model look-ahead

- dynamic search structured

- multipass search

- best-first search

- Weighted Finite State Transducers (WFST)

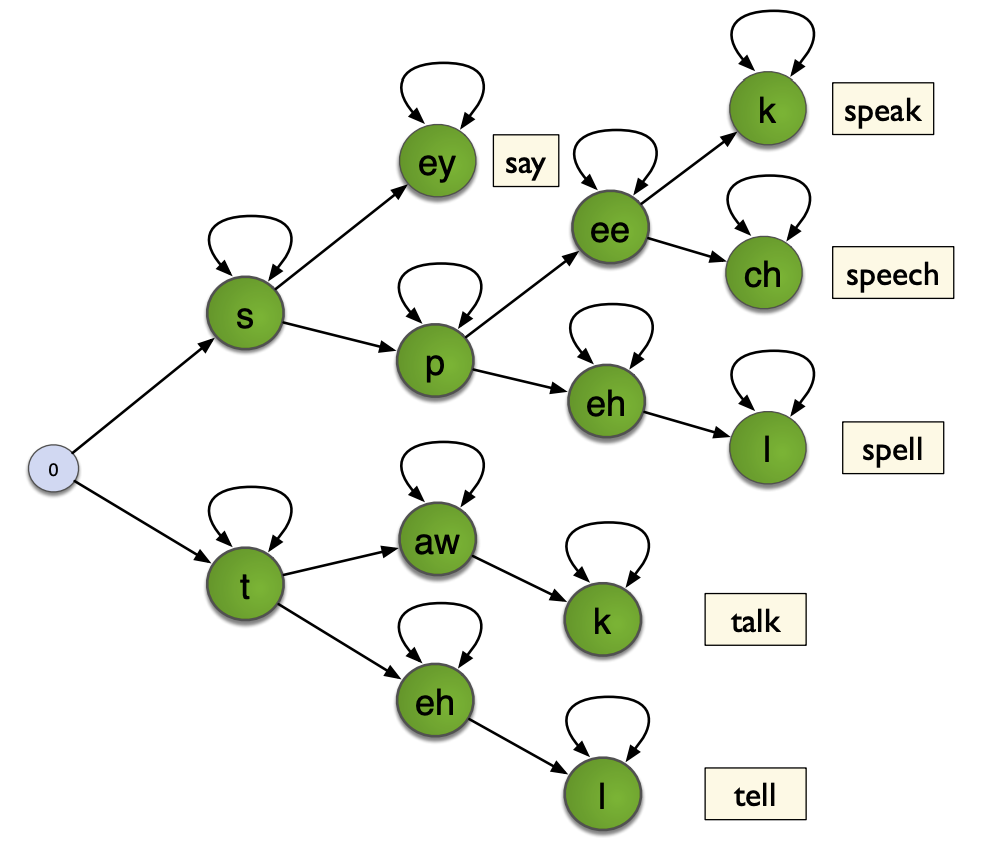

Tree-structured lexicons

In tree-structured lexicons, we represent the possible words of a language in a tree, nodes being phones, and leaves being words. Therefore, when we have a sequence of phones, we only need to follow the corresponding branch of the tree, which greatly reduces the number of state transition computations :

Language model look-ahead

In a tree-structured decoding, we look ahead to find the best LM scores for any words further down the tree, and states are pruned early if they lead to a low probability. This makes the decoding faster, since many branches are dropped.

Weighted Finite State Transducers (WFSTs)

WFSTs are implemented and used in Kaldi. WFSTs transduce input sequences into output sequences. Each transition has an input label, an output label, and weights.

Let’s get back to the basics.

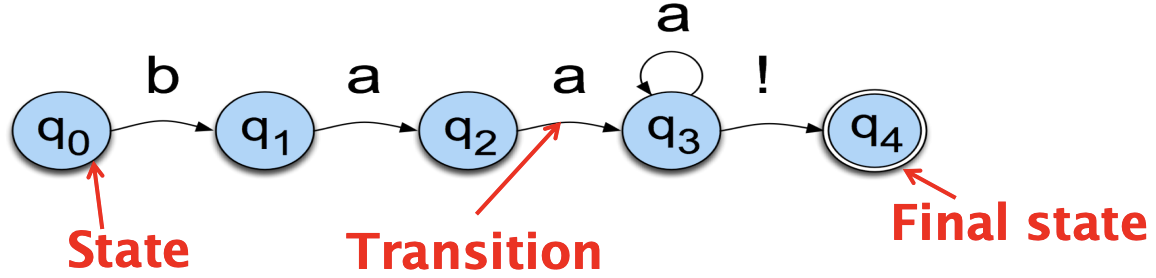

Finite State Automata

Finite State Automata (FSA) are extensively used in Speech. We define them as an abstract machine consisting of:

- a set of states \(Q\), with an initial one \(I\) and a final one \(F\), often called the accepting state

- a set \(Y\) of input symbols

- a set \(Z\) of output symbols

- a state transition function \(q_t = f(y_t, q_{t-1})\) that takes the current input event and the previous state \(q_{t-1}\) and returns the next state \(q_t\)

- an emission function \(z_t = g(q_t, q_{t-1})\) that returns an output even

You migh recognize here a more generic definition of Hidden Markov Models (HMMs). HMMs are in fact a sub-base of Stochastic FSAs. A path in FSA is a series of directed edges.

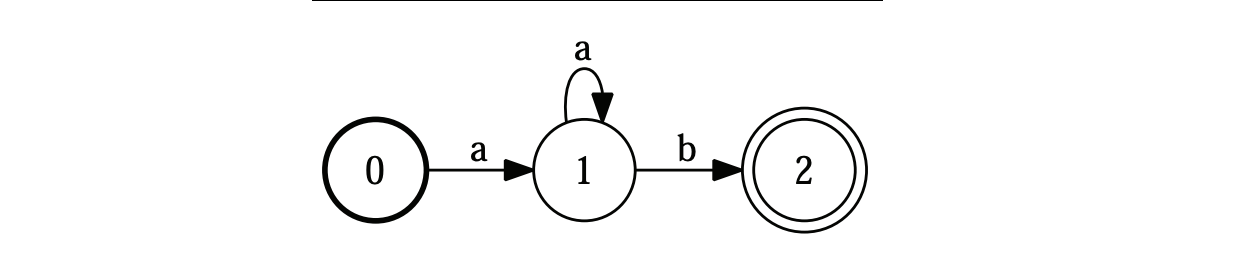

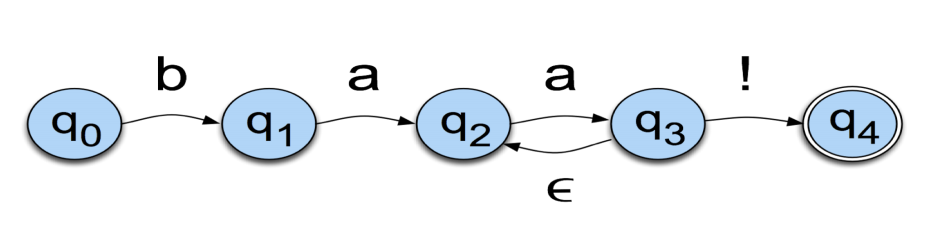

Let us conside the language of a sheep for example: /baa+!/. This language has 5 states:

The state labels are mentioned in the circles, and the labels/symbols are on the arcs. More formally, FSAs are usually presented this way:

Finite State Acceptor

In our sheep example, the alphabet is made of 3 letters: b, a and !. It has a start state and an accept / final state, as well as 5 transitions. FSA acts as an Acceptor, in the sense that it can reject a set of strings/sequence:

- abaa! is rejected because of the initial state

- baa!b is rejected because of the final state

- baaaa! is accepted

A string is accepted if:

- there is a path with that sequence of symbols on it

- the path is successful, starts at the initial state and ends at the final

An additional symbol that has a special meaning in FSAs is \(\epsilon\). It means that no symbol is generated. This is a way to go back to a previous state without generating anything:

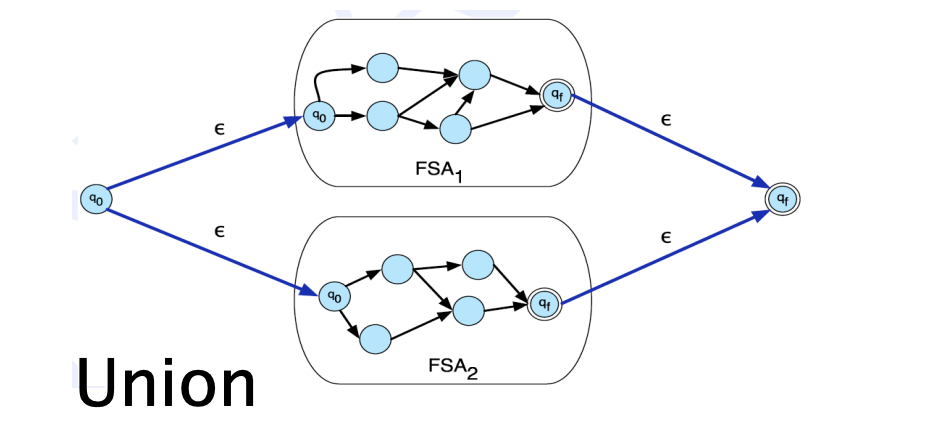

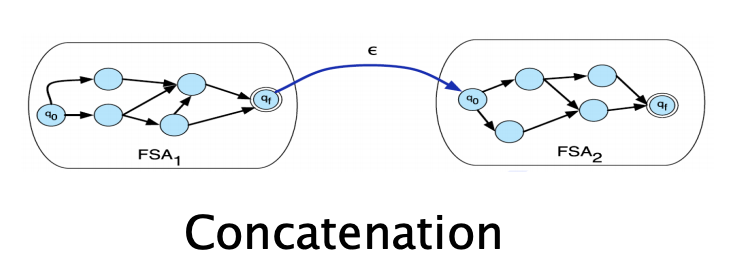

Composition of FSA

Formal languages are just sets of strings, and we can apply set operations on them. There are two main types of operations used on FSA and WFSTs:

- Union, or sum of two , denoted : \([[T1 ⊕ T2]](x, y) = [[T1]](x, y) ⊕ [[T2]](x, y)\)

- Concatenation, or product, denoted: \([[T1 ⊗ T2]](x, y)\)

- Kleene closure, which is an arbitrary repetition

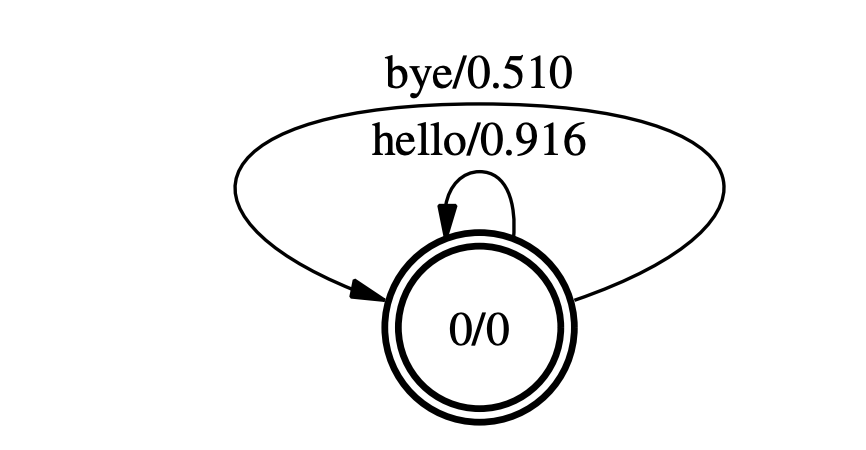

Weighted FSA

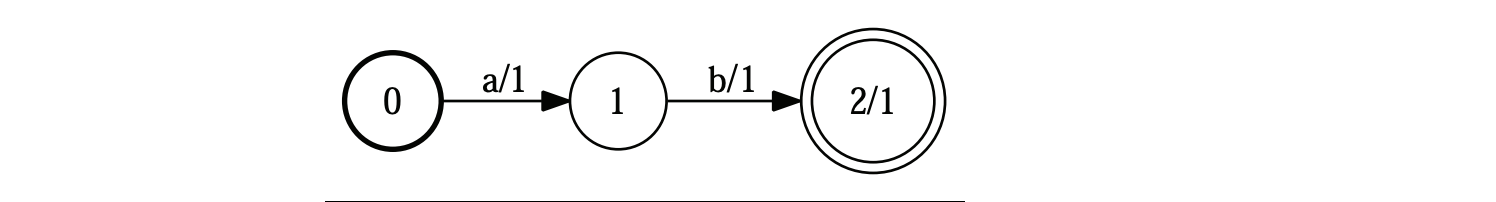

Weighted FSA simply introduce a notion of weights on arcs and final states. These weights are also refered as costs. The idea is that is multiple paths have the same string, we take the one with the lowest cost. The cost, on the diagram below, is represented after the “/”.

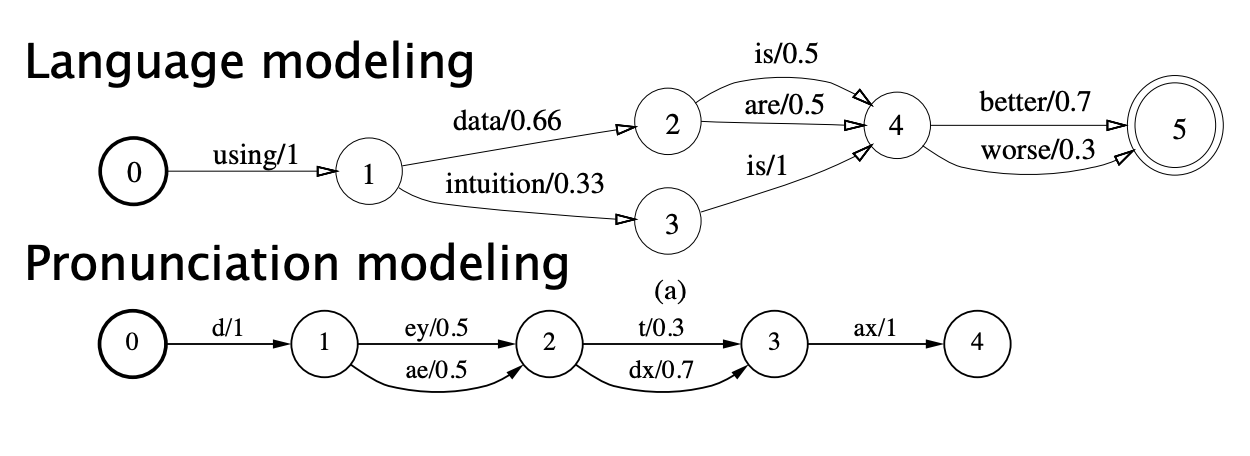

Weighted FSAs are used in speech, for language modeling or pronunciation modeling:

Weighted Finite State Transducer

Finite Automata do no produce an output, whereas Finite State Transducers (FSTs) have both inputs and outputs. Now, on the arcs, the notation is the following:

a:b/0.3

Where:

- a is the input

- b is the output

- 0.3 is the weight

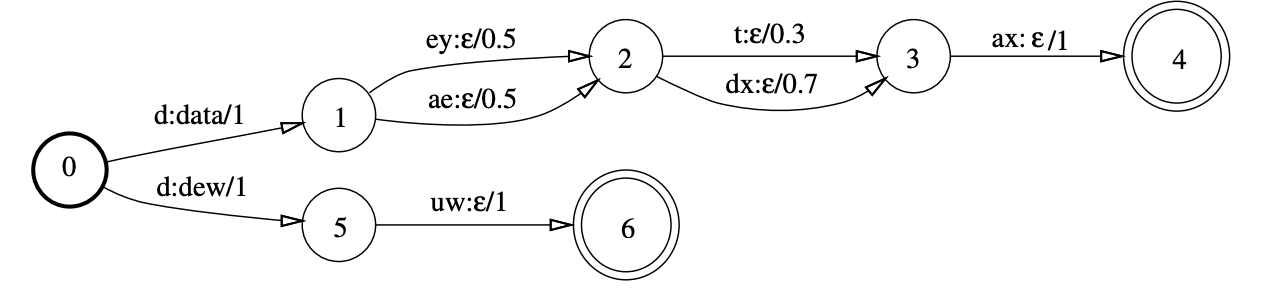

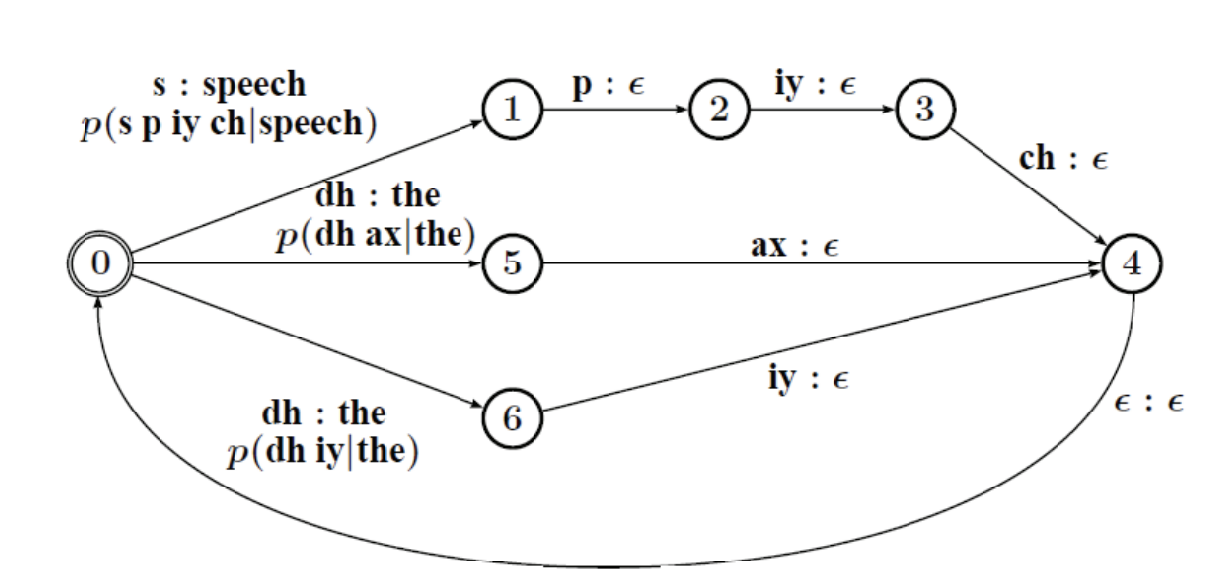

Why do we need to produce outputs? For decoding ! We can typically take input phonemes and output words.

In this example, the output word is mentioned as the output of the 1st input. In this example, from the phoneme “d”, we can build 2 words:

- data (deytax, daedxax…)

- dew (duw)

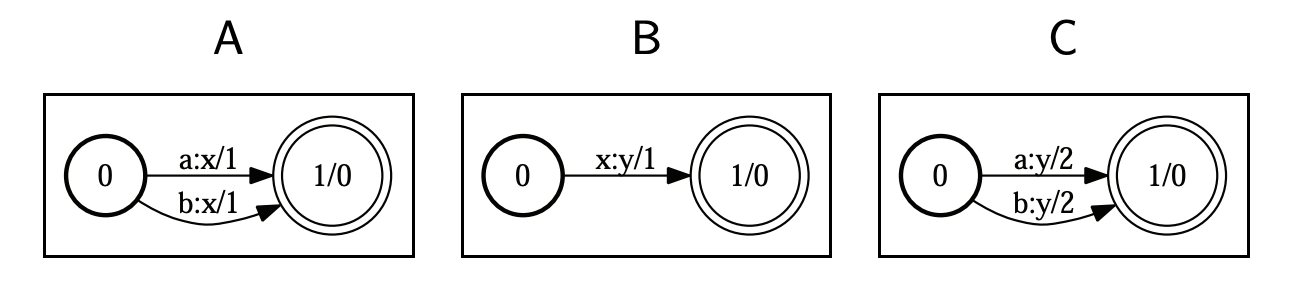

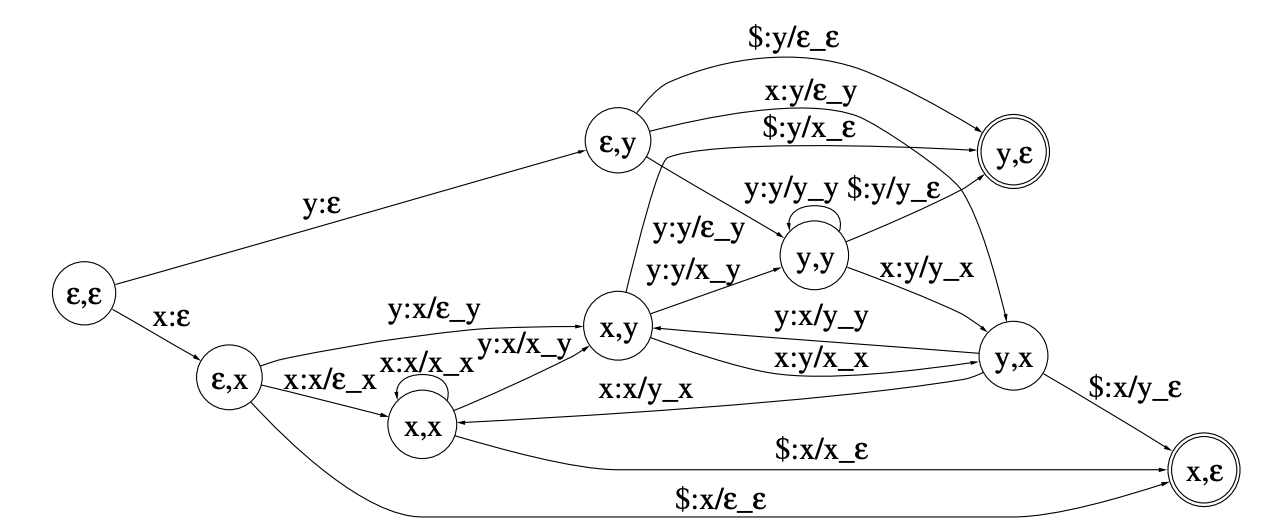

WFSTs can be composed by matching up inner symbols. In the example below, we match A and B in C, denote it C=A◦B, and since in A the inputs a and b and matched with x, and in b x is matched with y, in C, a and b are matched with y:

WFST algorithms

There are several algorithms to remember for WFSTs:

- composition: Combine transducers T1 and T2 into a single one, where T1 is passed as an input to T2.

- determinisation: ensure that each state has no more than a single output transition for a given input label.

- minimisation: transform a transfucer into a new one with fewest possible states and transitions

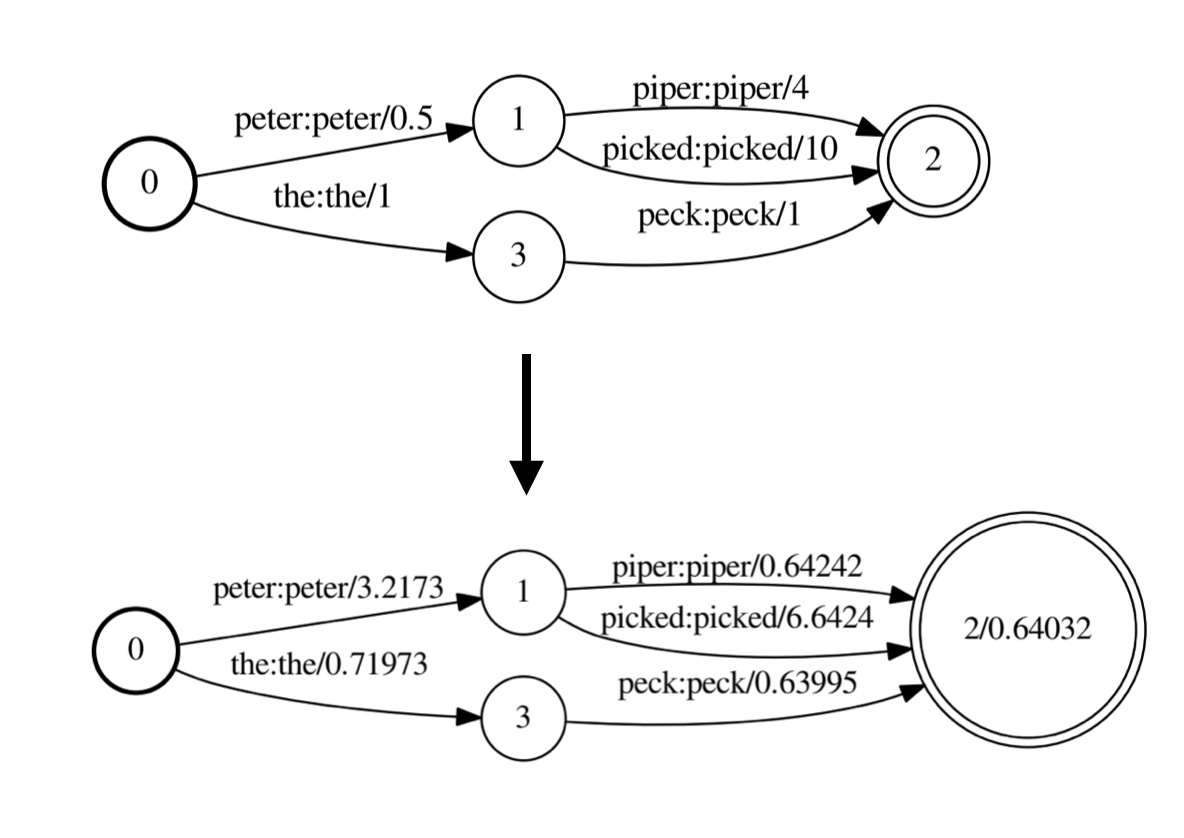

- weight pushing: push the weights towards the front of the path

The weight pushing process could be illustrated this way:

Decoding with WFSTs

The idea of the decoding network is to represent all components that allow us to find the most likely spoken word sequence using WFSTs:

HCLG = H◦C◦L◦G

Where:

- H is the HMM, that takes inputs HMM states and outputs context-dependent phones

- C is called context-dependency, takes context dependent phones as an input and outputs phones

- L is the pronunciation lexicon that takes phones as an input sequence and outputs words

- G is the language model acceptor, a transducer at the word-level that takes words as an input, and outputs words

All the components are built separately and composed together.

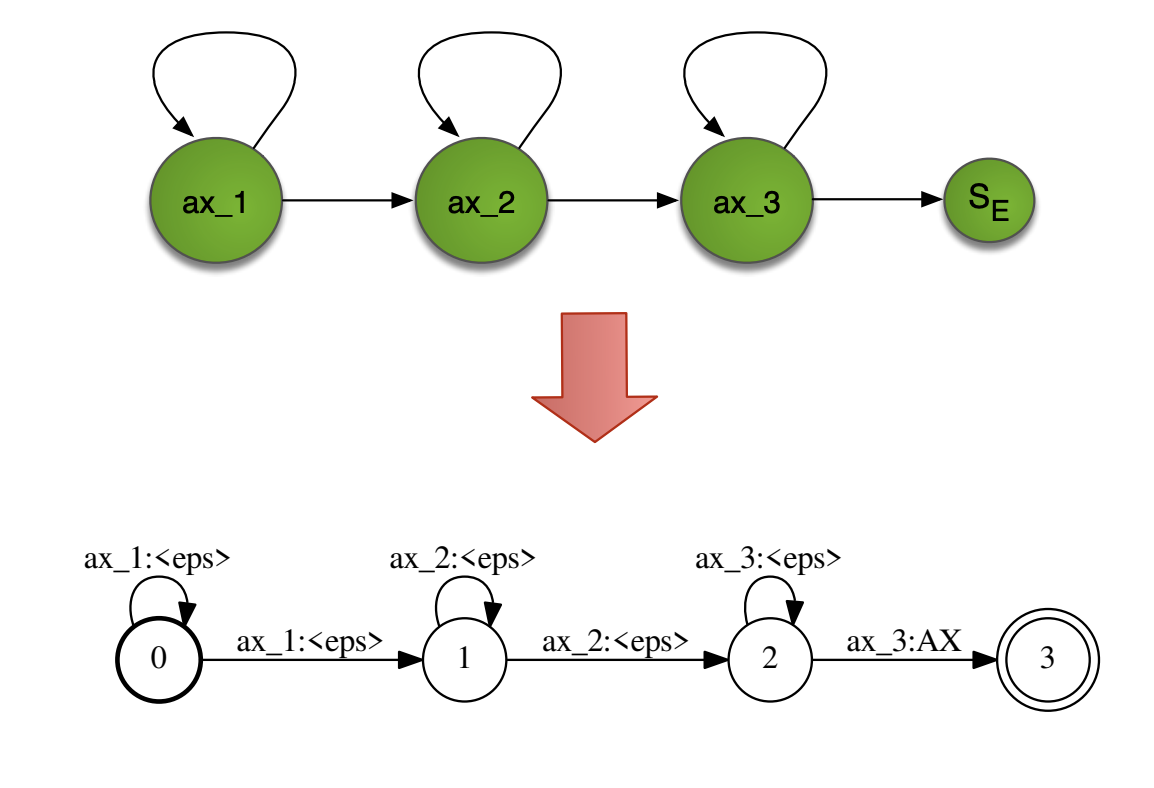

H: HMMs as WFSTs

HMMs can be represented natively as WFSTs the following way:

To avoid having too many context-dependent models (\(N^3\)), we apply what was mentioned in the HMM-GMM acoustic modeling: clustering based on a phonetic decision tree.

C: Context-dependency transducer

HMMs take into account context through context-dependent phones (i.e triphones). To feed it into the pronunciation lexicon, we need to build from these context-dependent phones a set of context-independent phones. To do that, a FST is built and explicits the transitions between triphones. For example, from a triphone “a/b/c”(i.e. central phone “b” with left context “a” and right context “c”), the arcs represent the individual phones “a”, “b”, “c”.

L: Pronunciation model

The Pronunciation lexicon L is a transducer that takes as an input context-independent phones and outputs words. The weights of this WFST are defined by the pronounciation probability.

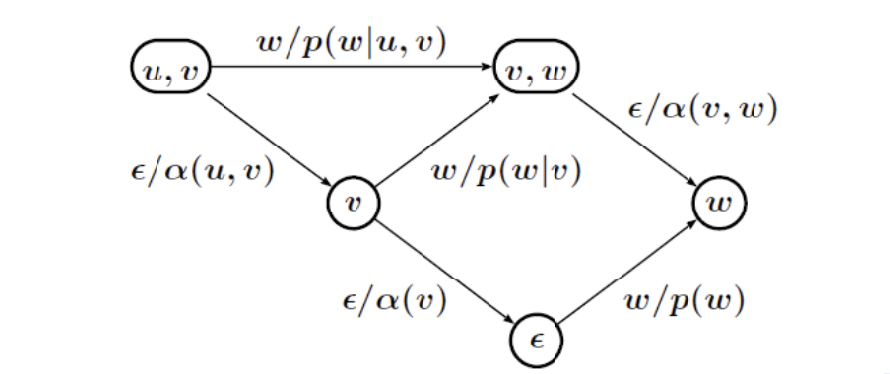

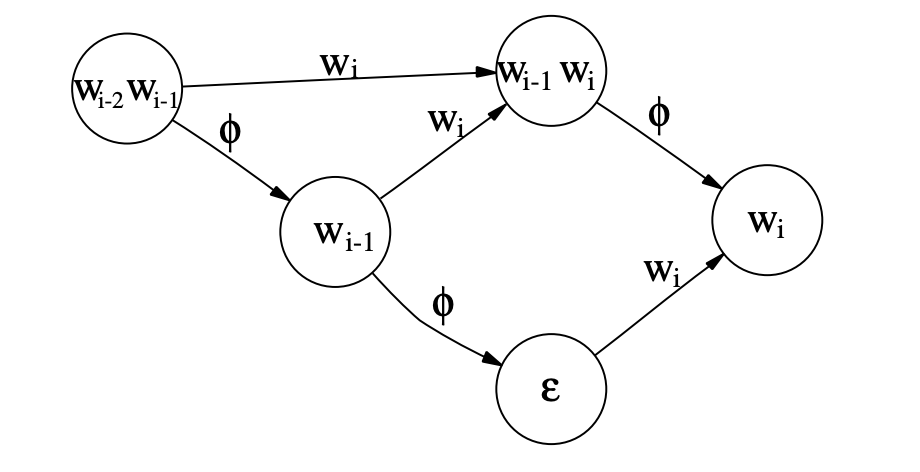

G: Language model as WFSAs

We can represent language models (LMs) as WFSAs easily too, and any type of LM will actually be implemented as a WFSA in Kaldi or other softwares. They do no produce any output, so they remain Automatas and not Transducers, since our aim is just to estimate the “cost” of a path.

In a unigram LM, the probability of each word only depends on that word’s own probability in the document, so we only have one-state finite automata as units.

In a bigram LM, the probability of a word depends on the previous word too, and in a trigram LM, on the 2 previous words. You would represents a trigram WFSA this way:

The decoding process

The different components of the deconding graph have now be explicited, and can be more formally defined as:

\[HCLG = rds(min(det(H ◦ det(C ◦ det( L ◦ G)))))\]Where:

- rds means remove disambiguation symbols

- min is the minimization (with weight pushing)

- det is the determinization

Conclusion

If you want to improve this article or have a question, feel free to leave a comment below :)

References: