Speaker biometrics is a field of Speech processing which focuses on identifying a unique speaker from several audio recorings. This can be useful for access control or suspect identification for example. Most of my understanding of this field was built from an excellent thesis, “Speaker Verification using I-vector Features” by Ahilan Kanagasundaram from Queensland University of Technology, and from the APSIPA Talk : “Speaker Verification - The present and future of voiceprint based security”.

What can you extract from speech?

Linguistic features, carrying message and language information:

- What is being said?

- What language is spoken?

Paralinguistic features, carrying emotional and physiological characteristics:

- Who is speaking?

- With what accent?

- Gender of the speaker

- Age of the speaker

- Emotion:

- Stress level

- Cognitive load level

- Depression level

- Spleepiness detection

- Is the person inebriated

Overview of Speaker Recognition

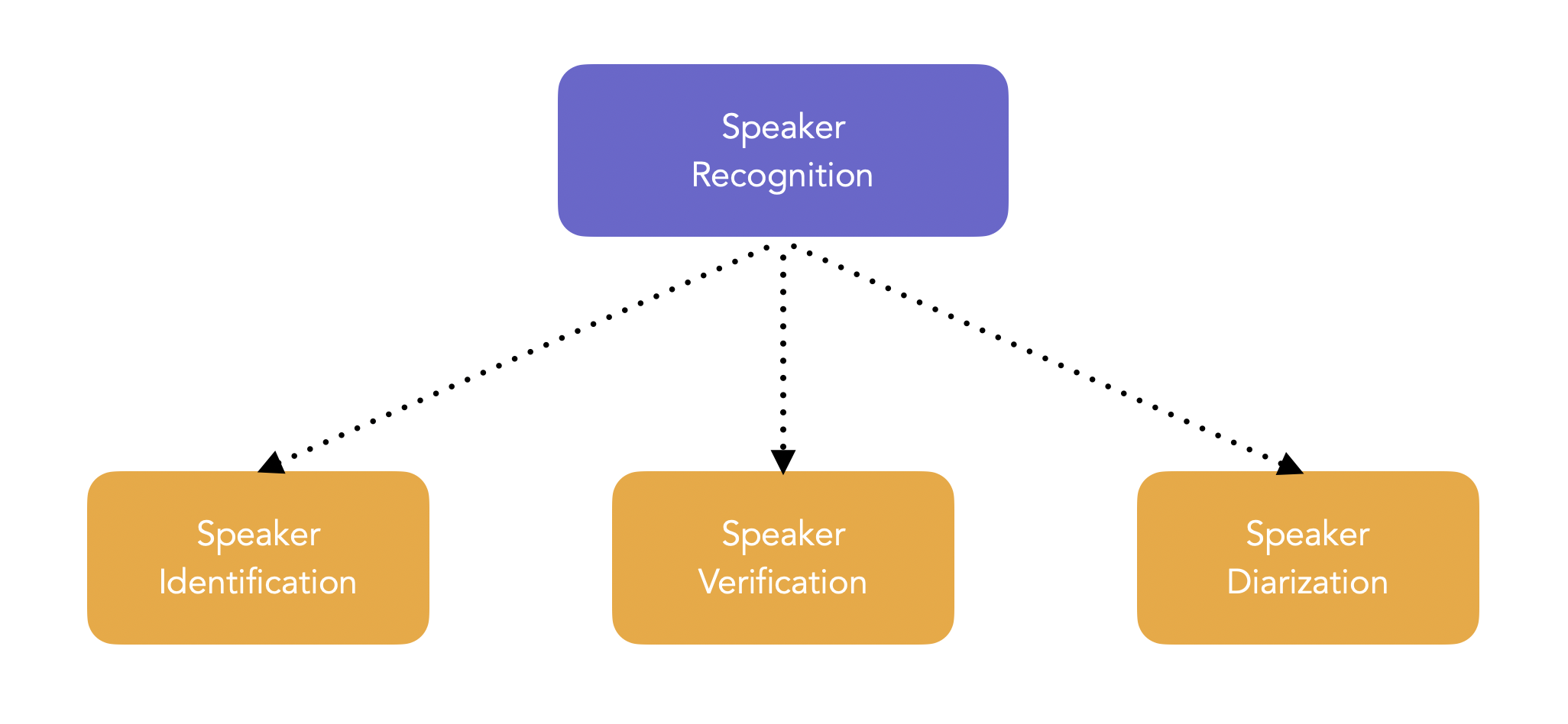

Speaker biometrics/recognition is split into:

- Speaker identification: determine an unknown speaker’s identify among a group of speakers. We take the audio of the unknown speaker, compare it to the models of all enrolled speakers, and determine the best-matching speaker.

- Speaker verification: verify the claimed identity of a person through speech signal. We compare the audio sample provided with the claimed speaker model, and decide to accept or reject.

- Speaker diarization: partition an audio input stream into segments according to the speaker identity.

Speaker verification is used in access security, transaction authentification and in suspect identification mainly, and is therefore the most commonly studied problem. This field has been an active field of research since the 1950s.

Overview of Speaker Verification Pipeline

Speaker verification aims at determining whether the identity of the speaker matches the claimed identify, and requires typically 1 comparison. On the other hand, speaker identification among a group of size N requires N comparisons.

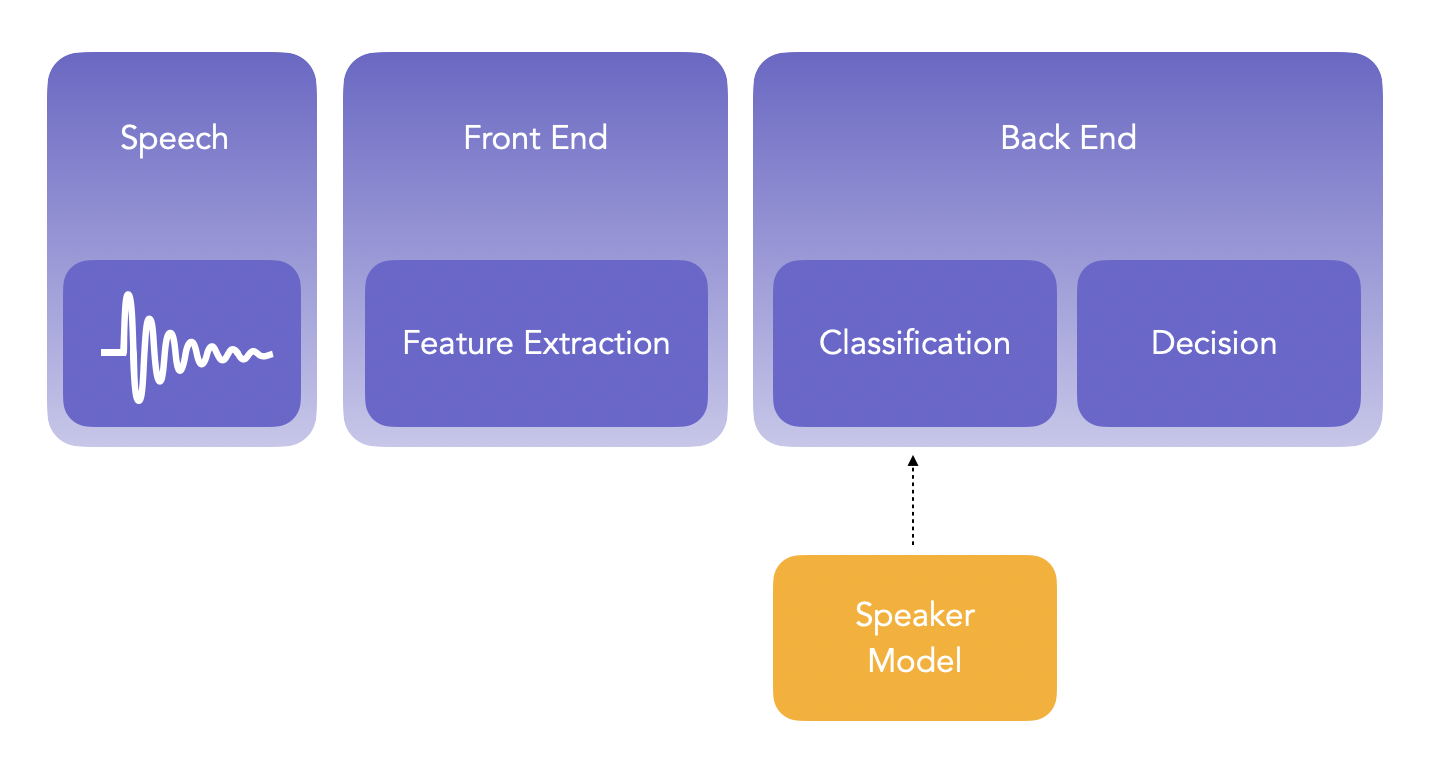

The main steps when running a Speaker Verification pipeline are the following:

- extract features from the audio in what is called the Front End

- compare those features to a speaker model in the Back End

- make decision based on the output

The main known issues in this field of research are:

- the amount of data needed

- the mismatch between the training data (enrolment) and the testing data (verification), since the channel might change (silent room vs noisy phone environment)

There are 2 types of speaker verification techniques:

- Text-dependent: the speaker must pronounce a known word or phrase. In such case, short training data are enough.

- Text-independent: users are not restricted to say anything specific. In such cas, the training data must be sufficiently long, but the solution is more flexible.

A common example of text-dependant speaker verification would be the “Hey Siri” of most iPhones now. The phrase to pronounce is known in advance, and we must verify the identity of the person. Once the identity has been verified, a Speech-to-Text pipeline translates what the user pronounced into a query.

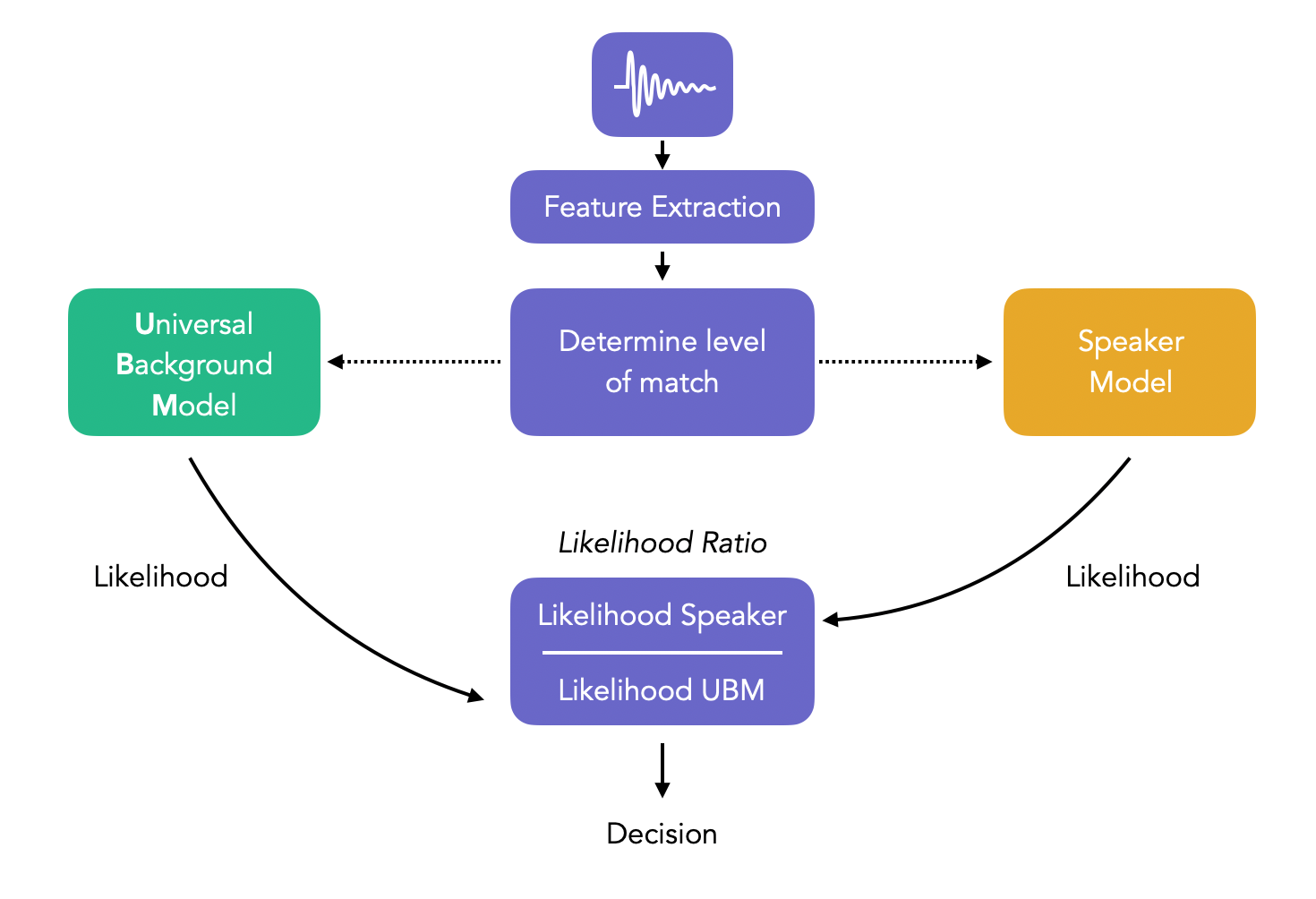

The main steps of speaker verification are:

- Development: learn speaker-idenpendent models using large amount of data. This is a pre-training part, called a Universal Background Model (UBM). It can be gender-specific, in the sense that we have 1 for Males, and 1 for Females.

- Enrollment: learn distinct characteristics of a speaker’s voice. This step typically creates one model per unique speaker considered. This is the training part.

- Verification: distinct characteristics of a claimant’s voice are compared with previously enrolled claimed speaker models. This is the prediction part.

The difference between the training and testing data might come from:

- the microphones

- the environment

- the transmission channel (landdline, VoIP…)

- the speaker himself

The decision process in classic Speaker Verification systems simply compares the likelihood that a speaker comes from the specific model and the likelihood that the speaker comes from the Universal Background model:

We call this ratio, the likelihood ratio. If the ratio is above the decision threshold, it is more likely that the sample comes from the specific speaker and we therefore accept the identity. Otherwise, we reject it. Note that the UBM might be gender-specific.